In part I of this article, we demonstrated that a reproduction of a well-known piece of art can become a registered trademark. Several examples of paintings were cited, namely works of Old Masters that have been monopolised by companies precisely by way of registering such works with the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO). It is worth considering, however, whether gaining protection for reproductions of well-known works of art can fulfil the market functions typically expected from a trademark at all.

It is commonly agreed that a trademark is supposed to distinguish goods or services of one company from those marketed by other companies. This means that the aim of applying for registration of a mark is to prevent other entities from using the same trademark for identical or similar goods or services. The distinctive function is what defines the concept of trademark, which means that a mark with no capacity to distinguish goods or services from others cannot, as a rule, qualify as a trademark. Obviously, beside the ability to indicate the origin of specific goods or services, a trademark can also fulfil additional market functions, such as evoking specific associations among target consumers — for example, with a particular product quality — and in that way build consumers’ trust in the product.

The question that now needs answering is: can a reproduction of a work of art fulfil the above-mentioned functions of a trademark in the course of trade? From a legal point of view, it is evident that a work of art can become a registered trademark as long as there are no absolute grounds for refusal to register a mark that comprises such a reproduction. It is worth considering, however, whether target consumers will be able, in normal market conditions, to link such a mark to the goods or products of a specific company. An art piece in itself intrinsically evokes specific associations, most commonly related to the author, the author’s oeuvre, or at least the art style or movement that it represents.

Let us refer once again to the example of “The Night Watch” by Rembrandt van Rijn. The question needs to be raised if the work, as a registered trademark, can bring the concept of particular goods from a specific company to consumers’ minds, the goods here being a metal, strontium (see: EUTM-016613903). If a series of marketing and advertising actions is implemented, such an outcome cannot be dismissed. Nevertheless, the first associations of those looking at such a trademark will always be related to the art of painting. In this case, the reproduction of a work of art registered as a trademark does not clearly indicate (unlike e.g. a company logo) the original source of goods or services bearing it (i.e. a specific company). Such associations first need to be instilled in target consumers under normal market conditions. It is also worth mentioning that, in general, works of art (except for literature) do not contain word elements, which are usually the first part of a trademark noticed by target consumers. In this context, a decision to register a well-known painting as a trademark first requires defining a clear strategy of how such a mark should be used in the course of trade. Otherwise, any exclusive right acquired might not meet the original commercial expectations placed on such marks.

In practice, the objectives of those applying for protection for reproductions of paintings tend to vary. This can be illustrated by the example of the “Lady with an Ermine” by Leonardo da Vinci. In 2001, the Princes Czartoryski Foundation, a branch of the National Museum in Krakow, applied to register a reproduction of the painting with the Polish Patent Office. As the owner of the painting at the time, the Foundation wanted to acquire exclusive rights to exploit its reproduction for financial gains to be derived from a number of goods and services in classes 6, 9, 14, 16, 20, 21, 28, 35, 41, and 42 of the Nice Classification. Since it is not possible to assert proprietary copyrights to the “Lady with an Ermine” (the portrait was painted in c. 1489, so it is not subject to copyright protection), registering a reproduction of the painting as a trademark would grant the proprietor legal monopoly over it.

Trademark according to application Z.236957 / Leonardo da Vinci, “Lady with an Ermine”

According to the data of the Patent Office, registration proceedings for the above figurative trademark were discontinued. We can only speculate as to what the grounds for such a decision were. In accordance with the applicable administrative procedure, proceedings are discontinued if they are found to be groundless for any reason. The Princes Czartoryski Foundation also applied for protection for the word mark “Lady with an Ermine” (Z-400801); however, the conditional decision that was given has already expired. This may suggest that in both cases the proprietor simply waived its right to protection for the two marks (a word trademark and a figurative trademark being a reproduction of a famous painting), having recognised that an exclusive right thus obtained would not eventually meet the proprietor’s expectations from a purely commercial point of view.

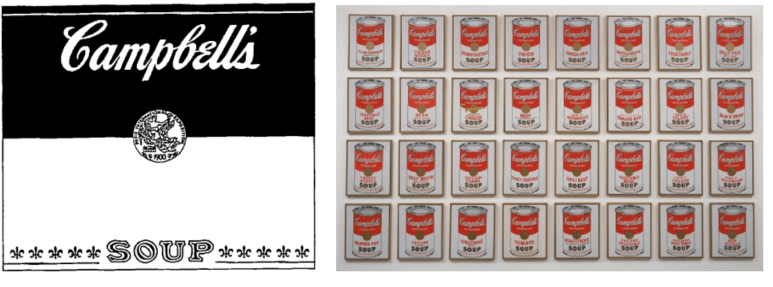

In the context of the subject of our discussion, another perspective should be adopted for contemporary works of art, which often elude any previous definitions of artistic expression. This can be illustrated by the example of a series of paintings titled “Campbell’s Soup Cans” by Andy Warhol, which show cans of soup that the artist himself is rumoured to have enjoyed quite frequently. Depictions of thirty-two soup cans were arranged by Warhol, one next to the other, creating an effect of multiplication of the main element, a characteristic feature of Warhol’s artistic style. It comes as no surprise, then, that the original design of the label placed on Campbell’s soup cans was registered as a Community trademark no. EUTM-000272914.

Trademark No. EUTM-000272914 / Andy Warhol “Campbell‘s Soup Cans” [source: www.moma.org]

Interestingly, Warhol’s 1962 painting is dated earlier than the first registration of trademarks depicting Campbell’s soup labels, which were made in 1965 (according to the data provided by the British Intellectual Property Office). In can therefore be concluded that in this case it was a detail of a piece of art that was subsequently registered as a trademark. However, it should be borne in mind that pop-art works, which addressed the subjects of consumerism and materialism, derived from various means of artistic expression typical for advertisements. Therefore, this style of art is closer to the nature of a trademark, which can be used as a marketing tool to promote specific goods or services.

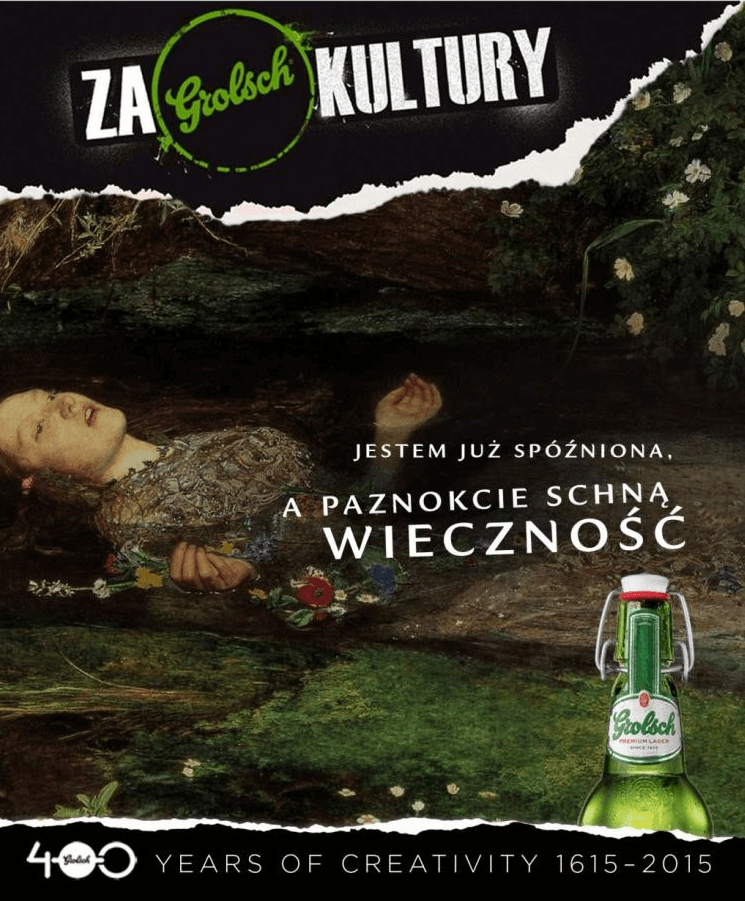

Finally, it is worth considering whether combining a reproduction of a famous work of art with an already registered trademark would not be more beneficial from a marketing point of view due to product placement. This idea was successfully explored by, among others, the Dutch “Grolsch” beer brand, which advertised its products using works of master painters creatively juxtaposed with slogans, a registered trademark (EUTM-000379552), and a fragment of the product packaging (a bottle).

“Grolsch” beer advertisement which uses the painting “Ophelia” by John Everett Millais

[source: http://mmponline.pl/artykuly/180133,grolsch-sadzi-urodzinowe-fiolki]

To summarise, although in general there are no formal obstacles to registering a reproduction of a work of art as a trademark, it should be asked first what one wants to achieve from a commercial perspective by doing so. Using a recognisable painting by a famous artist is no guarantee of success for a brand built around such a trademark. Everything depends on how a piece of art is used for the purposes of a trademark. As Thomas Edison used to say, to have a great idea, you need to have a lot of them.